In his new masterpiece “The Boy and the Heron,” Hayao Miyazaki returns from retirement to present an analysis of succession, grief, and choice.

At 82 years old, Hayao Miyazaki is not only one of the greatest directors alive, but also the world’s most deceitful retiree. Since 1997, Miyazaki has been announcing his retirement only to go back to the studio and return with another classic film, like when he retired and came back in 2001 for “Spirited Away,” retired, returned in 2013 for “The Wind Rises,” retired again, and is now back with “The Boy and the Heron.” Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki said in an interview that currently, Miyazaki “…thinks about the next project every day. I can no longer stop him.”

Released in the United States on Dec. 8, 2023, Miyazaki’s “The Boy and the Heron” follows 12-year-old Mahito, who struggles with his mother’s recent death, as he begins a new life at a village in the countryside. The traditional themes of wondrous Ghibli mythology begin to appear as Mahito meets a gray heron who introduces him to a fantastical world hidden in his backyard.

The film initially seems full of loose strings, much like a floating dream. However, at the end, the narrative is brought together with simple, honest perfection. Supported by an English-language cast consisting of Mark Hammil, Dave Bautista, Willem Dafoe, Florence Pugh, Christian Bale, Luca Padovan, and Robert Pattinson, who went full-out for his role, “The Boy” captures its audience as soon as the blue Ghibli screen is displayed.

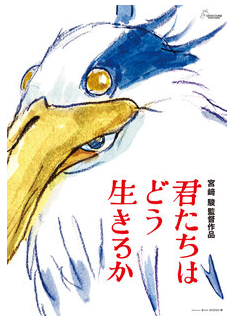

Surprisingly, “The Boy and the Heron” had no marketing campaign at all, save from a single poster in Japanese that displayed its original title: How Do You Live? The title’s translation, then, seems almost churlish in comparison to the original Japanese title, for it devoids the audience of the film’s most essential question: how does one live after being forever changed by tragedy? What is the extent to which grief shall be carried on, and where is the separation between wanting something back and carrying its weight forward?

With “The Boy,” Miyazaki displays his most profound –and seemingly last– love-letter to the public, but especially to his son Goro, with whom he has had a publicly complicated relationship and who has firmly declined the offer to take up his father’s role at the company. In “The Boy,” however, Hayao Miyazaki seems to let go of the idea of a perfect Ghibli succession, making peace with the consideration that his monumental creations may not continue in the same way after him.

Yet, as the film examines it, this change is not a problem. Miyazaki’s children are not him, and neither should they be expected to be. Miyazaki dismantles the idea of Studio Ghibli as a burden, and elevates it to an immortal monument of magic splendor.

Hayao Miyazaki has made references to his personal life throughout his career. His family, like the family of main character Mahito, manufactured rudders for fighter planes. Like the mother in “My Neighbor Totoro,” his mother also had tuberculosis. Like Setsuko in “The Grave of the Fireflies,” Miyazaki himself also had severe digestive problems as a child. In most of his films, the clash between industrious war machines and humanity is a common theme, as Miyazaki grew up during World War II. It is no surprise that his seemingly last film would be his most personal yet.

The ceaseless honesty and beauty of his work has paid off every time, and the same is true of his newest film. “The Boy and the Heron” has become the first original anime movie to top North American box-office and already earned Golden Globe nominations for best animated feature film and best original score.

And, in a period of AI “art,” “The Boy” is a victory for both the visual arts and the (indomitable) human spirit. The movie’s present success demonstrates that viewers are much more open to poignant and seemingly “difficult” films than the industry may think, and that endless remakes without any backbone or originality are undermining the public and underselling in the box-office. Hopefully, the success of “The Boy and the Heron” will urge the film industry to increasingly support and fund movies that take seven years and countless hours of hand-drawn animation, and in general any film that is ruthlessly personal, human, and original.

Hayao Miyazaki has successfully led “The Boy and the Heron” to reach out and take its deserved prestige amongst other Ghibli classics. If he decides to retire for good this time, the film will tie up his stellar portfolio with a golden, glittering bow. Nevertheless, it is safe to assume that Miyazaki will only stop making movies when he is physically unable to. And that’s a good thing.